Beneath the northern French town of Arras is a labyrinth of tunnels and caves that were used to help the allies defeat the Germans in The Great War. Those elaborate subterranean passageways hide an army of 25,000 British Soldiers right beneath the unsuspecting German army. From their hiding place beneath the front lines of that long ago war, the British were able to launch battles and raids from deep within the enemy territory.

Beneath the northern French town of Arras is a labyrinth of tunnels and caves that were used to help the allies defeat the Germans in The Great War. Those elaborate subterranean passageways hide an army of 25,000 British Soldiers right beneath the unsuspecting German army. From their hiding place beneath the front lines of that long ago war, the British were able to launch battles and raids from deep within the enemy territory.

In the years after the war these caves and tunnels were forgotten and built over. They have recently been rediscovered and escalated giving us an unequaled look into the world of the early 20th century warfare.

Next to a suburban supermarket, beneath a former camp site, the public can take a glass elevator from the 21st century straight down to the world of Tommy Atkins and bully beef.

Clever lighting and sound effects have created a mesmerising insight into life on the Western Front.

Accompanied by a bilingual expert and an excellent audioguide, parties of 20 are able to weave their way through an authentic slice of the Great War.

At the time, the Great War was considered the War to End All Wars. Of course, now we know that it was the war that began a series of wars in the 20th century. They didn't know that then. It is only in retrospect that we are able to see how one lead to the other. Its only in retrospect that we are able to learn the hard lesson that history taught us from that war. One of those lessons being that not ending the war by defeating the enemy only left us to have to fight the same enemy another day. It seems apparent to me that every war of the 20th century was a result of a lack of a proper ending to that war, including the Vietnamese and Korean wars. Yet, that war was quickly overshadowed by the second World War and many of the lessons learn were lost under the much larger and deadlier World War II.

At the time, the Great War was considered the War to End All Wars. Of course, now we know that it was the war that began a series of wars in the 20th century. They didn't know that then. It is only in retrospect that we are able to see how one lead to the other. Its only in retrospect that we are able to learn the hard lesson that history taught us from that war. One of those lessons being that not ending the war by defeating the enemy only left us to have to fight the same enemy another day. It seems apparent to me that every war of the 20th century was a result of a lack of a proper ending to that war, including the Vietnamese and Korean wars. Yet, that war was quickly overshadowed by the second World War and many of the lessons learn were lost under the much larger and deadlier World War II.

The Great War was the first modern war in which it was learned that frontal assaults were nothing less than suicidal.

The generals had learned a few lessons from the 1916 Battle of the Somme. Chief among them was the fact that frontal assaults on well-defended enemy trenches and artillery were mass suicide.

As the Western Front stalemate continued from the North Sea to the Swiss border, the French hatched a grand plan to win the war in 48 hours. They would smash through the German lines along the River Aisne in the spring of 1917.

The British would play their part with a colossal pre-emptive strike around Arras 50 miles to the north. A dazzling plan then took shape.

For almost a century, the ingenuity of the Battle of Arras has remained lost to our collective memories.

Today, Arras is an unremarkable town an hour's drive south of Calais. Most British tourists whizz past it on the autoroute as they drive to Paris and beyond. But if they look out of the window, they will glimpse some clues to the carnage in these parts.

Beautifully tended Commonwealth War Graves are dotted on either side. Soaring to the east is the stirring Canadian memorial to the 11,000 men who died in the heroic capture of Vimy Ridge. It is often said that Canada came of age as a nation that day.

Arras was a forlorn and battered frontier town. In 1914, it had been captured by the Germans, recaptured by the French and then put under British control to allow the French to concentrate elsewhere. In 1916, it was a shell of a place.

Civilians had been evacuated and British occupied the ruins while the Germans, who held the higher ground, sat to the East lobbing shells into the town.

It was just another stalemate situation on the Western Front. But, unseen by the Germans, something extraordinary was going on under the ground.

The plan to utilize the tunnels, sewers, cellars and caves created during the time of the Romans occupation was nothing short of ingenious. New Zealand Tunnelers were brought in to connect the caves, cellars and sewers with tunnels. In the end, it housed 25,000 allied troops. Five Hundred New Zealanders got the job done in record time. The entire plan was executed in complete secrecy.

Can you imagine the logistics of getting 25,000 soldiers down into those caves through a bakery? They managed to do it undetected. And there they waited until the appointed date to strict the Germans, Easter Sunday, 5.30am on April 9, 1917. They took the Germans completely by surprise.

Can you imagine the logistics of getting 25,000 soldiers down into those caves through a bakery? They managed to do it undetected. And there they waited until the appointed date to strict the Germans, Easter Sunday, 5.30am on April 9, 1917. They took the Germans completely by surprise.

The German guns, already hammered by their British counterparts, had little time to readjust their sights and bring fire down on an enemy which was suddenly a mile closer than anyone had expected.

There was heavy fighting, of course. Thousands of brave men, like Harry Holland, did not survive the day, but the losses were nothing like the Somme.

Germans surrendered bootless and still in night clothes. Up in the northern sector, around Vimy Ridge, the Canadians faced much stiffer opposition but they, too, had been helped by their own intricate tunnel arrangements leading up to the German lines.

Day One of the Battle of Arras was, without doubt, a great success. Within a couple of days, the Allies had advanced eight miles. By the woeful standards of that war, it was like capturing a continent.

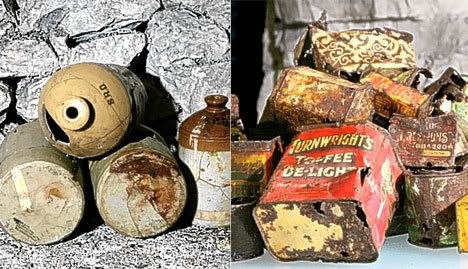

The war went on, but the Battle of Arras was a grand success in the context of the times. As the war and time went on, the tunnels were closed down, Arras was rebuilt and people forgot that day of bravery, sacrifice and grander. Some Frenchmen remembered the caves and used them again for shelter just a few short years later during the long hard days of World War II. Then, they were forgotten. In 1990, Alain Jacques began to investigate what had happened in that area during the Great War. He became curious when he couldn't find an answer as to why there were English words written on pillars and walls in that area. There was no written record of what had happened there. Studying the archives, he began to understand why places in that area were named names like 'Wellington'. That led to beginning of the excavations.

He had discovered the Blenheim quarry. Over the subsequent years, he would find much more. In 1994, a gas pipe repair led him to Thompson's Cave. Gradually, he worked out where the soldiers had emerged to meet the enemy.

His problem was that post-war Arras had simply expanded over the entire network and out into what had once been No Man's Land.

Much of the network has collapsed, much else is extremely unsafe and French laws meant that there could be no question of opening any museum underneath private homes.

Along with Arras's director of tourism, Jean-Marie Prestaux, Alain worked out that just one quarry - Wellington - had the potential for safe public access because it lay under a council-owned campsite.

Now, 18 years after Alain's first discovery, a £3 million visitor centre and a lift have been constructed. The Carriere Wellington, underground home of the Suffolk Regiment 91 years back, is, finally, open to the world.

"Everyone knows the Somme and Verdun," says Jean-Marie as he shows me round his beloved project.

"Now people from all over the world will learn of Arras. Even most French people know nothing of all this."

When I finally resurface, blinking and speechless, into the daylight, I ask Alain to show me where the inhabitants of Wellington would have emerged on that freezing dawn in 1917.

He takes me down several suburban streets, until we reach a crossroads on the Rue St Quentin.

"Here," he says, "this is where they came out to fight the enemy."

The scene could hardly be more poignant. Full of fun and laughter, it is a children's playground. Wherever he may be, I am sure poor Harry Holland would approve.

|